How Long Will This Madness Continue Oh Cataline

Contents

- Life and Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero

- Life of Cicero

- Works of Cicero

- Further resources

- Audio & Video

- Videos with English subtitles

- Audio of Latin text

- Latin text

- Vocabulary & Commentary

- English translation

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two millennia of gems in Latin. In this fifth chapter, we will learn more about the most famous Roman orator of all time: Marcus Tullius Cicero. We will also read the beginning of his most famous speech – his speech against Catiline –In Catilinam.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the preface here.

Life and Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero

In this section you will learn about Cicero and his works.

(106–43 B.C)

Cicero needs very little introduction, being one of the most famous Romans of all of antiquity. He was a politician, consul, a lawyer, a philosopher and one of Rome's greatest orators, and, of course, an avid letter writer.

Life of Cicero

Cicero's life is no small subject, and I shall not even attempt an exhaustive treatment of it here. Instead, we shall outline it, a sketch, if you will so that we can get a rough picture of this immensely famous and influential man.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in Arpinum, southeast of Rome, on the 3rd of January 106 B.C. to a wealthy equestrian family.

He was well educated in both Greek, philosophy, history, poetry, law and rhetoric. He studied philosophy under Philo of Larissa (c.159/8–84/3 B.C.), the head of Plato's Academy, law under politician Quintus Scaevola Augur (c.159–88 B.C.), and rhetoric under Greek rhetorician Apollonius Molon.

Coming from an equestrian family, the natural place for Cicero to start his career was the army. He soon left it to become a lawyer and his first major case (that we know of and of which there is still a written record) was his defense of patricide-accused Sextus Roscius. Roscius was acquitted and Cicero earned a reputation as a lawyer.

His first office was as quaestor in Sicily where he became very popular with the Sicilians. In fact, he became so popular that the inhabitants asked him to prosecute a magistrate, Gaius Verres, for misgovernment, to say the least. Cicero returned to Rome and did just that. He wrote four speeches In Verrem, only the first of which was delivered. Cicero won the case and, as a result, added to his reputation as a great lawyer but also becoming known as the greatest orator in Rome.

His next office was as an aedile, the following as praetor and in 63 B.C he was elected consul together with Gaius Antonius Hybrida, the uncle of Marcus Antonius.

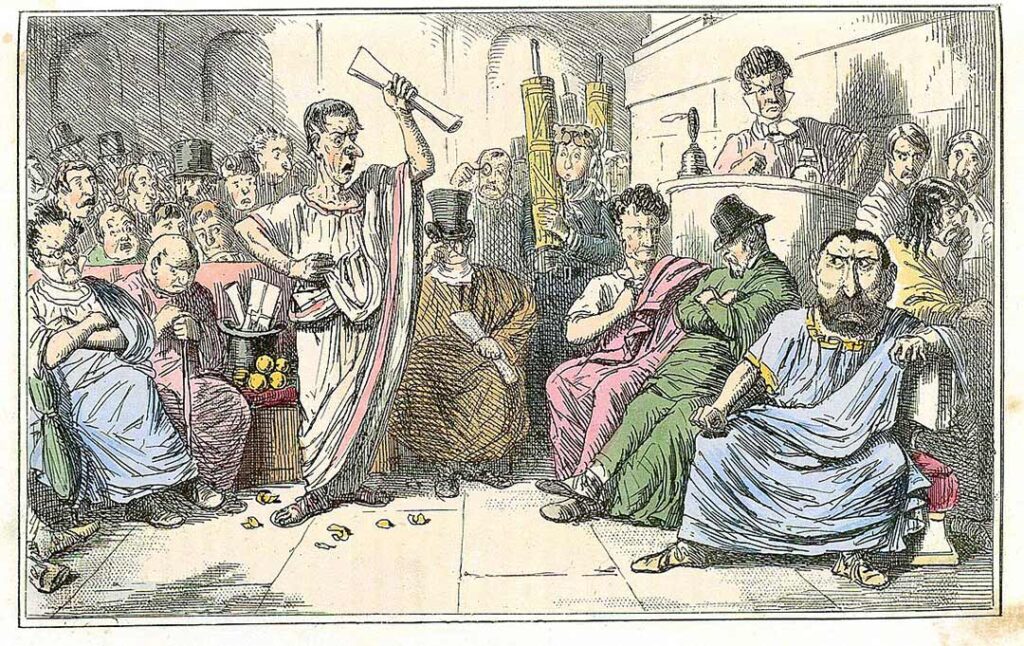

During his time as consul, he stopped the so-calledCatiline conspiracy, a conspiracy aiming to overthrow the republic and assassinate Cicero himself. The head of the conspiracy was Lucius Sergius Catilina, or Catiline (108–62 B.C.), hence the name of the conspiracy.

Cicero famously drove Catiline from Rome with four speeches. However, Catiline did not give up but instead began preparing an army while his followers, still in Rome, continued with their plans.

Long story short: Cicero found out and had five of the lead conspirators confess in front of the senate, at least according to the side of history we have access to, i.e. Cicero's and Sallustius' side. He then had them executed without a formal trial. (If you want the long story you can read more about this in Cicero's In Catilinam, 3, and in Sallustius' Bellum Catilinae, 46–55.)

Five years later, in 58 B.C. Publius Clodius Pulcher, tribune of the plebs, backed by the Triumvirate (i.e. Julius Caesar, Pompeius Magnus, and Marcus Licinius Crassus, a partnership Cicero had been invited to, but turned down), threatened to exile anyone who executed or had executed a Roman citizen without trial.

Cicero, having done just that during the Catiline conspiracy, was forced into exile and went to Thessalonica, Greece. We know from letters to his friends and family, that this time in exile hit him hard. He was depressed, miserable, even on the brink of suicide (see for ex. his letters to his family, Fam. 14.4.4., and to his friend Atticus, Att. 3.3, 3.4, 3.7).

After a year, the senate recalled Cicero from exile and he returned to Rome where he tried to re-enter politics but ended up concentrating on his literary pursuits instead.

After a few years, he accepted the office of proconsul in Cilicia, Turkey, for a year.

During all this time, the struggle between Pompeius Magnus and Julius Caesar had intensified immensely. Cicero avoided openly criticizing and alienating Caesar, but he did favour Pompeius Magnus as he believed him to be on the side of the Republic in which he ardently believed.

Then Caesar crossed the Rubicon.

Cicero fled Rome and joined Pompeius. War ensued.

After Caesar's victory at the battle of Pharsalus, Cicero returned to the city and was pardoned.

In February 45 B.C. Cicero's daughter Tullia died. He mourned her greatly, hid from the public eye and wanted nothing but solitude. He wrote several letters to his dear friend Atticus about his grief and about how he wrote and read to distract himself from his mourning. (see e.g. Att. 12.14–16) He even wrote a philosophical work called Consolatio to ease his pain. This work is now lost to us, but fragments of are quoted by Lactantius (c.250–c.325) in his Institutiones Divinae.

When Caesar was murdered on the Ides of March the following year, Cicero was not part of the conspiracy. But he did become a popular leader in the aftermath of the assassination. However, Marcus Antonius was also a popular leader and they became opponents, nay, bitter enemies. At the end of this struggle, Cicero was declared an enemy of Rome. He was hunted down and executed the 7th of December 43 B.C. in Formiae.

Works of Cicero

Cicero's life may be interesting and exciting, but it is his literary and stylistic legacy that really gets the blood pumping.

His influence on the Latin language has endured for millennia.

Cicero was instrumental in transforming the Latin language from a practical, straight-forward language to a language that could be used as a literary medium, a language with which abstract thoughts could be expressed.

His skill in rhetoric and his use of the Latin language made him an ideal, someone to look up to, not only in his own time, but well into our times.

Quintillianus perhaps said it best:

"[Cicero] is not the name of a man, but of eloquence itself."

— Institutio Oratoria, 10.1.112

Cicero, his works, and his language led to the admiration from the Church Fathers and he was declared a so-called "virtuous pagan" by the Early Christian Church. A "virtuous pagan" was someone who during their life never had an opportunity to recognize Christ, but still led a good life. This meant that many of his works were preserved, studied, treasured and copied, whereas many other Roman authors' works were not.

However, not all works were preserved in their entirety but have been reconstructed from fragments. Luckily it was not only the Early Christian Church and her followers that studied, copied and quoted Cicero, but Roman and medieval writers as well. His worksDe Re Publica (On the Republic) andDe Legibus (On the laws) especially were quoted from all sides, which means that it has been possible, to a large extent, to recreate them.

Sadly though, as with many Roman authors, many works of Cicero's have been lost to time.

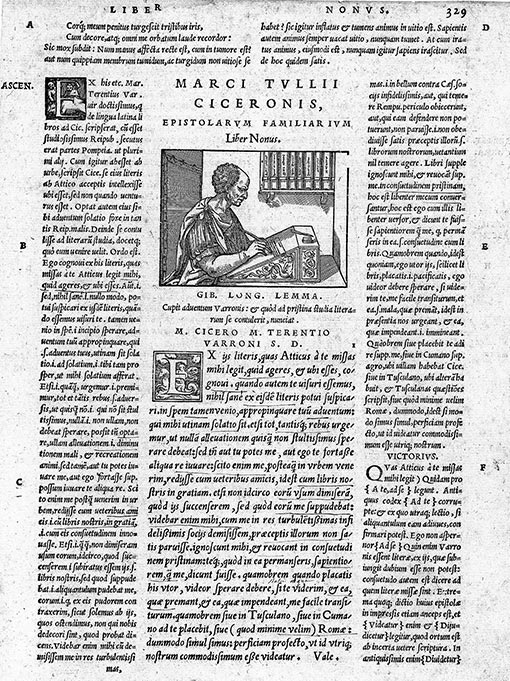

One of the most impressive collections we have from Cicero is his letters. 37 books of his letters exist today, we know of 35 more which, unfortunately, have been lost. These letters are written to and from family, friends, and various public figures. They give great insight into both the Latin language, but also into Cicero's life and the history of late republican Rome.

In 1345 Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374) found Cicero's letters to his dear friend Atticus,Epistulae ad Atticum, in the Chapter Library of Verona Cathedral. No one knew they were there. This discovery, some scholars mean, sparked the beginning of the Renaissance.

Cicero became so associated with the classical Latin language that a select number of renaissance scholars decided that if a word or a phrase did not appear in one of Cicero's works it should not be used. This is famously and brilliantly ridiculed in Erasmus' Dialogus Ciceronianus .

Cicero was not only important for the renaissance humanists' relationship to the Latin language or for our historic knowledge of Rome, but also for his influence on, as mentioned, rhetoric, politics, and philosophy. Works such as De Inventione, De Devinatione, De Fato, De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, de Senectute, de Amicitia, de Officiis, as well as the abovementioned De Re Publica and De Legibus had great impact on scholars, politicians, and philosophers and their ideas throughout history.

To give you an idea of just in how high a regard Cicero's works have been held, here are two examples:

- When Johannes Gutenberg introduced the printing press he began with printing two books: Donatus' Ars Minor, and the Bible. But when it was time for a third, he chose none other than Cicero' workDe officiis.

- On May 8th, 1825, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to Henry Lee explaining what he was aiming for when he drafted the Declaration of Independence. In the letter, he gives us the sources he used for the draft: "All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c." (Note: Locke was himself an admirer of Cicero).

For students of Latin, Cicero has been, and is, perhaps most known for the many speeches he gave, and wrote down, as a lawyer and as a politician. Not all of them have survived history, but out of 88 known, over 50 have been preserved to this day, giving us an enormous well of elegant, creative, and enjoyable Latin, as well as insight into both the legal and the political scene of ancient Rome.

As we mentioned earlier, during Cicero's consulship, theCatiline conspiracy emerged, wanting to overthrow the government and assassinate Cicero himself. With his famous four flaming speeches, Cicero drove Catiline from the city, and in this chapter of2000 years of Latin Prose we will dig into the first part of the first speech, held in November 63 B.C.

In it, Cicero begins by asking a row of rhetorical questions to Catiline and then points out the absurd: that Catiline lives! Despite many men having been put to death for less, Catiline, planning the destruction of the government, still lives! O tempora, o mores!

Further resources

If you want to hear and read more texts from Cicero, we have recorded the following: Cicero's story about fraud, Cicero on the ring of Gyges, Two letters from, Cicero, Cicero on true and perfect friendship, Quid Cicero de ludis circensibus sensit? What did Cicero feel like going into exile?, and Cicero's quest for the tomb of Archimedes.

You can find them all in our our Latin audio archive.

We also have a video about when Cicero went looking for Archimedes' tomb (you can also find the story without explanations as an audio file above)

Another video about the story of Canius who wanted to buy a villa from CicerosDe Officiiswhere Daniel will read the text and explain difficult parts in Latin, you will find the pure audio file of the text above in the text about fraud.

We also have a video where Daniel goes through two passages fromDe senectute.

Want to know more about Cicero? Listen to these audio files about Cicero from Carolus LhomondsUrbis Romae viri illustres in our Latin audio archive.

If you want to learn even more about Cicero, especially about his works, style, and influences, I strongly recommend Michael von Albrecht's A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius.

Audio & Video

Click below to read and listen to a passage from Cicero'sIn Catilinam.

Videos with English subtitles

Audio of Latin text

Latin text

Below you will find the original text of the passage from In Catilinam in Latin.

In Catilinam, I.I

Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra? Quam diu etiam furor iste tuus nos eludet? Quem ad finem sese effrenata iactabit audacia? Nihilne te nocturnum praesidium Palati, nihil urbis vigiliae, nihil timor populi, nihil concursus bonorum omnium, nihil hic munitissimus habendi senatus locus, nihil horum ora voltusque moverunt? Patere tua consilia non sentis, constrictam iam horum omnium scientia teneri coniurationem tuam non vides? Quid proxima, quid superiore nocte egeris, ubi fueris, quos convocaveris, quid consilii ceperis, quem nostrum ignorare arbitraris?

O tempora, o mores! Senatus haec intellegit. Consul videt; hic tamen vivit. Vivit? immo vero etiam in senatum venit, fit publici consilii particeps, notat et designat oculis ad caedem unum quemque nostrum. Nos autem fortes viri satis facere rei publicae videmur, si istius furorem ac tela vitemus. Ad mortem te, Catilina, duci iussu consulis iam pridem oportebat, in te conferri pestem, quam tu in nos omnes iam diu machinaris.

An vero vir amplissumus, P. Scipio, pontifex maximus, Ti. Gracchum mediocriter labefactantem statum rei publicae privatus interfecit; Catilinam orbem terrae caede atque incendiis vastare cupientem nos consules perferemus? Nam illa nimis antiqua praetereo, quod C. Servilius Ahala Sp. Maelium novis rebus studentem manu sua occidit. Fuit, fuit ista quondam in hac re publica virtus, ut viri fortes acrioribus suppliciis civem perniciosum quam acerbissimum hostem coercerent. Habemus senatus consultum in te, Catilina, vehemens et grave, non deest rei publicae consilium neque auctoritas huius ordinis; nos, nos, dico aperte, consules desumus.

Below you will find some keywords and comments on the text.

These following words are key to understanding the text, if you already know them — great! — if not, make a mental note of them.

abutere: This is the future indicative of the deponent verb abutor. Abutere is the alternative form to the common abuteris.

caedes, is f. :murder, slaughter

concursus, ‑us m.:running together, gathering

constringo, ‑ere, ‑strinxi, ‑strictum: bind, restrain

effrenatus, ‑a, ‑um: unbridled, unrestrained

fuit ista…virtus: there was such virtue that…

furor, ‑oris m.:madness, frenzy, rage

iam diu machinaris: you have been planning. The present tense is used when the action begun in the past continues into the present.

iam pridem: a long time ago

iussu:by order

pateo, ‑ere, ‑ui:lie open

praesidium, ‑ii n.:guard, garrison, protection

Quam diu etiam? How much longer?

Quo usque? Up to what point?

tandem: at last, here, "May I ask?" or sim. Tandem with questions often adds a tone of impatience.

telum, ‑i n., projectile

English translation

Below you will find an English translation of the text.

In Catilinam I.I

When, O Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our patience? How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end of that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now? Do not the nightly guards placed on the Palatine Hill—do not the watches posted throughout the city—does not the alarm of the people, and the union of all good men—does not the precaution taken of assembling the senate in this most defensible place—do not the looks and countenances of this venerable body here present, have any effect upon you? Do you not feel that your plans are detected? Do you not see that your conspiracy is already arrested and rendered powerless by the knowledge which every one here possesses of it? What is there that you did last night, what the night before— where is it that you were—who was there that you summoned to meet you—what design was there which was adopted by you, with which you think that any one of us is unacquainted?

Shame on the age and on its principles! The senate is aware of these things; the consul sees them; and yet this man lives. Lives! aye, he comes even into the senate. He takes a part in the public deliberations; he is watching and marking down and checking off for slaughter every individual among us. And we, gallant men that we are, think that we are doing our duty to the republic if we keep out of the way of his frenzied attacks.

You ought, O Catiline, long ago to have been led to execution by command of the consul. That destruction which you have been long plotting against us ought to have already fallen on your own head.

What? Did not that most illustrious man, Publius Scipio, the Pontifex Maximus, in his capacity of a private citizen, put to death Tiberius Gracchus, though but slightly undermining the constitution? And shall we, who are the consuls, tolerate Catiline, openly desirous to destroy the whole world with fire and slaughter? For I pass over older instances, such as how Caius Servilius Ahala with his own hand slew Spurius Maelius when plotting a revolution in the state. There was—there was once such virtue in this republic, that brave men would repress mischievous citizens with severer chastisement than the most bitter enemy. For we have a resolution of the senate, a formidable and authoritative decree against you, O Catiline; the wisdom of the republic is not at fault, nor the dignity of this senatorial body. We, we alone,—I say it openly, —we, the consuls, are waiting in our duty.

Translated by C. D. Yonge (1856)

Source: https://latinitium.com/2000-years-of-latin-prose-cicero/